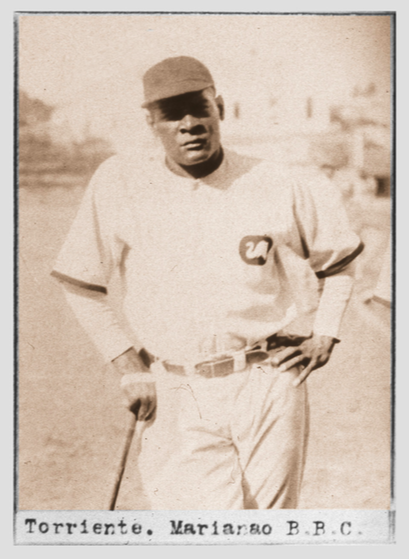

Cristóbal Torriente

“I think I was playing third base at the time, and he hit a ground ball by me…. It dug a hole about a foot deep on its way to left eld. … In those days Torriente was a hell of a ballplayer. Christ, I’d like to whitewash him and bring him up.” — Frankie Frisch (quoted by John B. Holway, Blackball Stars)

The legends and hyperbole — like Frankie Frisch’s report of a batted ball excavating the infield turf — repeatedly trump the solid factual evidence emerging from much of Cuba’s prehistoric era during the final two nineteenth-century decades and initial two twentieth-century decades. We possess the all-too-alluring images provided by fading sepia photographic portraits and dog-eared collectible tobacco cards. There are indeed substantial collections of sketchy box scores and skeletal line scores provided by chroniclers like Severo Nieto and Raúl Diez Muro — as notable for their inconsistencies and glaring inaccuracies as for any substantial record of dimly remembered turn-of-the-century winter-season pennant races. Holes are sometimes only partially filled by enthusiastic contemporary journalistic reports that are (as was the tenor of the times) far more celebratory than anything else. In the end the frustration is always that — in the words of American songstress Kate Wolf — “the picture on the cover doesn’t match the one inside.”

Modern-era researchers haven’t provided all that much to improve the picture. Tampa-based Jorge Figueredo (a sports journalist in Cuba before the 1959 revolution) has done the most to fill in gaps in our knowledge with his detailed statistical summaries and efforts at narrative chronicles for the turbulent decades that comprised Cuba’s professional-winter-league saga.1 But when it comes to resurrecting individual ballplayers, the best of our chroniclers have too often settled for sometimes outlandish fables gleaned from octogenarian stars of the past invested in turning their own careers and those of rivals into the heady stuff of pure folklore. John B. Holway (Blackball Stars) repeats legends of Torriente line drives digging two-foot holes in infield turf, or of Martin Dihigo outdoing a cesto-using jai alai player with his throws from home caroming off the center-field wall, and of Mule Suttles smashing a 600-plus-foot homer into the wind in Havana’s La Tropical ballpark. James Riley (The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues) cannot resist echoing reports that José Méndez once killed a teammate in practice with an errant fastball to the chest, or repeating the oft-quoted lines of Indianapolis manager C.I. Taylor that “If I should see Torriente walking up the other side of the street, I would say, ‘There walks a ball club.’” Enticing testimonials, but in the end a bit too reminiscent of tales of Josh Gibson home runs struck in Pittsburgh and landing in New York, or of Cool Papa Bell snapping a light switch and landing in bed before the electricity dimmed.

Of the three greatest Blackball-era Cuban icons, Martin Dihigo owns the most substantial legacy, due in part to his well-documented performances both in Mexico and in the United States with the Alex Pompez Cuban Stars. But mostly Dihigo benefited from the fact that the bulk of his long career fell in the better-documented winter and summer Cuban, Mexican League, and Negro League seasons of the 1930s and 1940s. José Méndez stands on the thinnest ground, suffering from an injury-shortened career that restricted his greatest achievements as a pitcher to little more than a single decade in which the bulk of his heroics came in an “American Season” limited to exhibition barnstorming games. Slugger Cristóbal Torriente boasts a greater North American Negro League legacy than Méndez as far as we can tell, but little of the Torriente story can today be documented with much certainty. The highlight North American years for Torriente came at outset of Rube Foster’s Negro National League when the Cuban slugger paced the Chicago American Giants to three initial league pennants while reportedly batting .411, .338, and .342.2 But much of his career was a vagabond journey with a dozen different clubs that was plagued by a penchant for nightlife and excessive drinking and was marked by several personal disputes with club managements that cut short a stopover with the Western Cuban Stars in 1916 and also saw him abandoning the Kansas City Monarchs a decade later after a dispute over some stolen jewelry.3

The Buried Legacy of Cuba’s Greatest Slugger

If there are troubling inconsistencies attached to Torriente’s North American Negro League statistics or occasional conflicting reports in slim existing narratives covering his on-field prowess, worse still is the fact that next to nothing is known about Torriente away from the baseball diamond — a gapping void that clouds his legacy still further. Biographical data boils down to a mere handful of consistently reported facts. He was born on November 16, 1893, in the seaport city of Cienfuegos. (One undocumented source suggests the location was a rundown house at 17 Hernan Cortés Street.) He died 44 years later in a pauper hospital in New York, only a half-dozen years after his playing career dissipated with the Atlanta Black Crackers and Cleveland Cubs in the summer of 1932. There are also suggestions that before fading into total obscurity in New York the hard-luck athlete had resided at least briefly in Ybor City, Florida (a Tampa district), and also that (as reported by Holway among others) fellow Cuban stars Rodolfo Fernández and Martin Dihigo had found him in “poor circumstances” in Chicago sometime in the mid-’30s. Holway reports that it was in fact Dihigo who relocated Torriente to New York for his final years of poverty and illness. We have no information regarding parents or siblings, and no clues about childhood years in Cienfuegos — except for a single undocumented report by Holway that the future ballplayer had joined the army at age 17 and “was assigned to the artillery because he was husky enough to hoist the heavy artillery pieces onto the mules.”4

About the origins of baseball activities we know only slightly more, although the record is hardly complete. His career was launched as a 17-year-old southpaw pitcher and part-time outfielder with the local Yara Club that claimed a juvenile district amateur championship in 1910. He moved on two years later to a semipro Cienfuegos team for which– like the North American Bambino to whom he would so often be compared in the future — his heavy hitting caused abandonment of pitching assignments and solidified his role as a cleanup slugger and outfielder. At age 20 he entered the island’s top professional circuit, debuting on January 5, 1930, with the Habana Reds and hitting .265 in 28 rookie-season games. A year later he moved over to the Almendares Blues, for whom he would perform for five seasons (excluding two winters when he apparently remained in the States throughout the winter months and skipped games in his homeland). After Almendares he returned to the Havana Reds for the bulk of an extended Cuban League career stretching through 1927. His two full decades with stateside Negro League clubs opened with Tinti Molina’s Western Cuban Stars (1913-1916), peaked with seven seasons (1919-1925) starring on Rube Foster’s Chicago American Giants, and included stopovers with nearly a dozen other clubs, although none of those additional sojourns lasted more than a year or two.

The key source for much of the Torriente legend — or at least the mainstream popularity of that legend — can be traced directly to the writings of John Holway. Holway focuses his laudatory account on a single game at the heart of a much celebrated 1920 “American Season” Havana tour by John McGraw’s National League New York Giants, a barnstorming event most famed for the single appearance on the island of the legendary Babe Ruth. Ruth — perhaps intent more on the attractions of Havana night life than any serious offseason slugging — had a rough time against Cuban competition right from the start. He smacked both a single and triple in the opening game with the Havana Reds, yet was struck out three consecutive times by cup-of-coffee Cuban big leaguer José Acosta in the second contest of the series.

But it was the third memorable outing, against Almendares on November 5, 1920, that would find a permanent spot in winter-baseball lore. That was the game in which the muscular local favorite Torriente would smack three towering homers and thus provide heroics seemingly more Ruthian than anything offered by the original Babe himself. Holway is elaborate in his descriptions, stressing the trench-digging groundball that almost cost Frankie Frisch a leg at third base, describing how “the Bambino frowned incredulously” when the Cuban slid into second after his soil-excavating hot liner, and then describing the three Torriente round-trippers as prodigious smashes clearing the left-center-field fence. Ignored or at least discounted was the fact that the Giants “batting practice” hurler that day was not a regular big-league twirler but instead first baseman George “High Pockets” Kelly. Also missing in Holway’s narrative are the contemporary press accounts that tell a very different story about that afternoon’s ballpark histrionics.

Both a substantial North American Negro Leagues career mostly with the Chicago American Giants, and a respectable tenure in the Cuban League have too long been altogether overshadowed (as underscored by Torriente’s bronze Cooperstown plaque) by the amplified accounts of that single afternoon in spacious Almendares Park. Three homers were struck by the Cuban, to be sure. But Roberto González Echevarría– relying on the Havana press accounts of the day — has effectively put the lie to the mythic status of Torriente’s lionized one-day slugging feat.5 The three long blasts off the unpolished pitching of Kelly were all of the inside-the-park variety (the fences were largely unreachable in Almendares Park, where the center-field barrier stood almost 600 feet from home plate) and were likely unenthusiastically pursued by hung-over Giants outfielders. Kelly had apparently volunteered for mound duty on a lark and while Ruth in relief did give up the infamous groundball double, he did not allow one of the homers often reported by enhancers of the legend. A local press account cited by González Echevarría suggests that Giants pitchers were not taking most of the games on the tour very seriously, were in truth lobbing “batting practice tosses” at the Almendares hitters, and were at any rate probably on the day of Torriente’s heroics still feeling the effects of excessive partying the previous night.

If mythical trappings infused into more mundane ballpark events have done almost as much to deflate as to elevate Torriente, we also perhaps need to raise an accompanying and equally pesky historical distortion. This is the legend touting the early twentieth-century Cuban winter circuit as somehow representing a legitimate Golden Age of domestic island baseball. This unfortunate reigning portrait of pre-revolution Cuban baseball is nowhere more celebrated than in Roberto González Echevarría’s widely circulated 1999 volume The Pride of Havana. And here is perhaps the biggest skeleton in the closet. The Cuban league of the first half of the twentieth century — so often romanticized as Cuba’s baseball epicenter — was in truth largely a ramshackle affair. Often it wasn’t a league at all but merely a short-season tournament, often featuring as few as three teams and perhaps fewer than two dozen games. Seasons were rarely long enough even in the most extended campaigns to provide reliable individual statistics; sometimes the winter seasons were even canceled or curtailed due to economic stress or political unrest. The playing fields were of low quality by modern standards and the competition always uneven. There were indeed a handful of top Blackball stars (mostly American) and later a sprinkling of big leaguers seeking wintertime work. But the significant big-league presence came long after Torriente and Méndez were gone from the scene, only after the end of mid-1940s hostilities with Jorge Pasquel’s player-raiding Mexican League, and after inclusion of the Havana circuit under the umbrella of Organized Baseball. In brief, the pre-World War II Cuban winter circuit was hardly a league on which to base much in the way of big-league quality credentials.6

It is now almost a platitude that early twentieth-century Negro ballplayers suffered numerous injustices. Their past glories inarguably need to be resurrected and they deserve their long-overdue recognition in the game’s annals. We are indebted as fans of the sport and consumers of its history to those who have labored to set the record straight by arduously searching archives of the nation’s once prolific African-American press. But at the same time we must here keep the historian’s eye sharply focused. The game’s past must be recorded with rigor and not turned over to enthusiasts with a “reconstructionist” agenda of their own making. Resurrecting Blackball history should not hinge on the kind of sloppy “scholarship” churned out by writers like William McNeil who through easy “hocus pocus” methods develop shoddy mechanisms for measuring and enshrining midcentury Cuban leaguers.7 To be rejected out of hand are lame efforts like McNeil’s to elevate Torriente and others by merely transforming their batting and pitching numbers (registered in shorter island seasons) into the precise length of standard big-league seasons, without ever so much as considering relative evidence about the playing conditions or quality of opposition such batsmen and hurlers were actually facing.

In a rather remarkable sleight of hand, McNeil informs us that according to his ingenious “conversion factor,” Cristóbal Torriente would have been reasonably expected to smack 17 homers and hit .329 annually in the big leagues (presumably the 1920s and 1930s big leagues of his own era, but that is not specified). Delightful magic if you can stomach it. According to this same unscientific method we might have projected that 2014 American League Rookie of the Year José Abreu (based on his best seasons in a contemporary Cuban League likely far stronger than the four-team circuits Torriente performed in) should have smacked 63 round-trippers in his debut campaign with the Chicago White Sox. Not a very insightful metric but all too characteristic of the less than rigorous enthusiasm of many of today’s most ardent Blackball boosters.8

Was Torriente, alongside Méndez and preceding Dihigo, part of the greatest group of Cuban players ever produced? He may well have been, through the argument now becomes especially difficult in the light of the achievements on big-league diamonds of a handful of modern-era stars stretching from Liván and El Duque Hernandez to Abreu, Puig, Chapman, and Céspedes. If Méndez mesmerized vacationing big leaguers for a handful of celebrated exhibition outings at most limited to three winters, Chapman has proven unhittable over a half-dozen big-league seasons in one of the sport’s greatest offensive eras. If Torriente batted well over .300 and slugged a few seemingly impressive homers in several dozen poorly reported short-season barnstorming circuits, Abreu and Céspedes have slugged away against the best of big-league hurlers in the heat of arduous 162-game pennant races.

Torriente’s Cuban League legacy is certainly impressive, even if sometimes distressingly thin. He boasts a legacy certainly the equal of the one attached to Méndez, even if he didn’t enjoy quite the same hometown icon status earned by the “Black Diamond” with those politically charged early-century triumphs over big leaguers representing occupying American forces. His record as a hitter is largely unparalleled in his own era. He owned the third highest overall batting mark in league history (.352 in a dozen campaigns), trailing only Americans Jud Wilson (.372 but only six seasons) and Oscar Charleston (.360 across a full decade). Other records include an unsurpassed five times as leader in triples, four times as the home-run leader (although his high was four in 1923 due to the immense league parks), and twice as batting champion. And there were accounts of Torriente’s remarkable defense as a rocket-armed center fielder that supplement holes left by missing or spotty statistical records. One can question (and perhaps should question) the level of competition in an era that witnessed no major leaguers on Cuban soil for regular league games outside the exhibitions of the staged early-winter American Season.9 But that argument can be raised whenever one compares different leagues or eras. Any player must be judged by where he stood against the competition at hand, and Torriente seemed to rank well ahead of most of the field he faced.10

Why in the end, then, does a biographical sketch of Torriente, reputedly one of the greatest of all Cuban sluggers and now a certified Cooperstown inductee, divert into a debate about the valuation of resurrected and reconstructed Negro statistics, the scant availability Negro League records and reliable firsthand game accounts, or the likelihood of overestimations of a pre-World War II Cuban winter league? In large part, of course, simply because there is so little else to pursue and so little else to add to the discussions of the void that is in large measure the sum total of the mysterious ballplayer’s underreported and under-documented career. But more importantly, such debates become centerpieces of the Torriente story precisely because they seem in the end to constitute his greatest legacy. Even more than his almost equally shadowy Cuban contemporary José de la Caridad Méndez, Torriente is remembered far more for what we don’t know, for what has consequently been invented or elaborated, than for what is found in verifiable records or documented events.

Torriente in the end suffered multiple blows from the unfortunate timing of his birth and from the segregated baseball universe into which he was accidentally born. He was denied by his skin color the chance to perform on the main stage of North America’s prestigious professional leagues. He thus achieved his greatness not only in the shadows of stateside outlaw Negro leagues ignored by a mainstream White press, but also in a Cuban winter circuit that was largely off the radar for the game’s North American center of gravity during the era in which he played. And when he did finally reach Cooperstown in a belated single-year effort (2006) to enshrine an entire bucket load of long-overlooked Blackball legends, his bronze plaque would trumpet a single renowned moment of his career (outslugging Babe Ruth during the Bambino’s 1920 barnstorming tour of Havana) that was little more than an unfortunate distortion of actual events. Unfair as it may be, Torriente’s bronze plaque on the walls of Cooperstown would seem to cast him into the all-too-large collection of the game’s shakiest fabrications, a cherished myth meriting a place alongside Doubleday’s 1839 miraculous-conception invention of American ballplaying, the Babe’s 1934 World Series “called shot” in Wrigley Field, Bonehead Fred Merkle’s single-handed loss of the 1908 pennant, or Jackie Robinson’s sanctioned solo role in the sport’s hard-won racial integration.

The Mysterious Burial of a Legendary Ballplayer

If Fate’s existing blows to a legitimate or lasting reputation were not sufficient, an even more painful irony has now arisen to besmirch the sketchy Torriente legacy. The largest amount of ink recently devoted to this lost Blackball legend is now being expended not in any strenuous efforts at uncovering actual on-the-field accomplishments, but rather to ongoing internet debates about the circumstances surrounding his final unfortunate days in a New York paupers’ hospital, the ambiguous circumstances surrounding the disposition of his human remains, and the equally mysterious location of his long-ignored bones. If the ballplayer remained lost to mainstream White baseball fandom while he lived, his final resting place today appears to be equally lost to those wishing to celebrate his murky legend.

The small phalanx of Negro baseball enthusiasts might well be excused for their somewhat odd focus given the scarcity of any other leads to pursue about who the living Torriente actually was. But it seems nonetheless a final unwarranted blow to Torriente’s legacy that the major efforts are not now being directed toward peeling away overblown legends and replacing them with more substantial documentation, but are instead being focused on resurrecting Torriente as a cause célèbre because he might be the only Cooperstown Hall of Famer without a properly marked gravesite.11

It was long common knowledge (or so we assumed) that within months of his lonely passing in New York the destitute former ballplayer’s remains were spirited away to his homeland for proper ceremonious interment by the pre-revolution Fulgencio Batista government. But that charming piece of folklore now appears to be only the final piece of distracting mythology attached to Torriente’s star-crossed legacy.

Dedicated Negro Leagues researcher Ryan Whirty wrote on his popular blog site in January 2016 about the revealing discoveries of fellow sleuths Ralph Carhart and Gary Ashwill (including the newly discovered official Torriente death certificate tracked down by Carhart in New York City archives) that combine to suggest the Cuban’s remains have in truth never been removed from their mass grave location in New York City. That location appears to be Calvary Cemetery in Queens, where the body may well have originally been dumped along with those of perhaps16 other nameless paupers when the penniless Torriente succumbed to the ravages of alcoholism and TB on April 11, 1938 (at age 44). Torriente is now known to have spent his final several painful years at the Riverside Hospital on the city’s North Border Island in the East River. The existing death certificate (which this author has seen)12 verifies a primary cause of death as pulmonary tuberculosis and the burial place as the Calvary Cemetery, a truly massive facility owned by the New York Catholic Archdiocese and reported to contain more than three million remains (the largest number of any cemetery in the United States).

Confusion over the true location of the ballplayer’s body only arose when stories circulated in Cuba (but were never well documented) that within two years (supposedly in 1940) the body was exhumed and removed to the homeland at the joint request of future President Fulgencio Batista and Cuban Sports Ministry director Jaime Mariné. What followed was supposedly an official enshrinement in the Colon Cemetery on the heels of Torriente’s election to the 1939 inaugural class of a new Cuban Baseball Hall of Fame. Yet there is no concrete evidence of the reinterment and much speculation exists that the report may have been circulated on the island merely to prop up the popularity of the powerful army colonel who had effectively been controlling the government for much of the previous decade (after the overthrow of dictator Gerardo Machado in 1933) but was now officially running for the presidency (which he indeed won) in 1940.

Whirty’s central aim was to discount the long-standing and seemingly apocryphal story that the newly empowered Batista government actually returned the bones to Havana for relocation in the Colon Cemetery, supposedly as centerpiece for a newly erected monument devoted to multiple legendary Cuban ballplayers.13 But Whirty further attempts to link the events surrounding the ballplayer’s fate to a 1938 assassination attempt aimed at strongman Batista (himself a mulatto) and involving a similarly named white-skinned Havana politician (Cosme de la Torriente). His efforts — in this final case perhaps more valuable in the long run — also extend to uncovering Torriente’s lost family connections at the end of the nineteenth century in the southern port city of Cienfuegos.

One line of inquiry pursued by Whirty — largely in an effort to locate a living relative who might perhaps aid in efforts to open the reported New York grave for possible revealing DNA testing — involves a wealthy nineteenth-century Cienfuegos family involved in the sugar-processing trade, a family with the reported surname Torriente. Whirty links this family through marriage to a de la Torriente clan that just might be connected with the assassination plotter in Havana, drawing a potential link to Batista and the glimmer of a theory about why the Cuban government might have initially “turned its back on one of its great ball-playing heroes at the time of his death.” (Of course the idea that the Batista regime abandoned Torriente to the fate of an unmarked pauper’s grave in New York directly contradicts the unproven reports that the Cuban government did in fact have the ballplayer exhumed and returned to the Cuban capital.) Whirty speculates that the Black ballplayer just might have been directly related to an unknown slave on the Cienfuegos sugar plantation owned by wealthy Spaniard Esteban Cacicedo Torriente — a slave who might (as often happens) have formally adopted the sugar baron’s hereditary family surname.

But there are flaws in the theory from the start. Foremost is the fact that the surname of the sugar mill owners was not the final name of Torriente but the middle name of Cacicedo. Spanish double last names feature the surname (patriarchal name) and then the mother’s name. It thus seems that even if the slave theory were plausible the ballplayer’s adopted family surname would have been quite different. Furthermore, the whole thesis about Batista plotting to have the dead ballplayer interred in a monument at the Colon Cemetery is itself just as seriously flawed, at least as reported, since the ballplayer monument that does indeed feature a relief bust of Torriente (alongside those of Méndez and Antonio García) was not yet there at the time. The pair of tombs erected by the Association of Christian Ballplayers were built in 1942 and 1951, well after Torriente’s death and original New York interment.

The real mystery begging resolution for the legions of fans interested in recapturing the sport’s pioneering years and its lost Blackball history is in the end, of course, not at all where the bones of the long-dead Torriente may actually reside. A more pressing issue seems to be recovery of details surrounding the substantial lost (and thus also buried) career behind the embellished legends that prop up Torriente the onetime ballplayer. It is not so much where the man is buried that so puzzles, but instead where the true outlines of the living ballplayer have somehow been buried by excessive myth-making and the voids and vagaries of our lost Blackball history.

Faced with a sparsity of reliable records and compelling firsthand accounts that reach behind the hagiography, it today seems that well-meaning amateur historians and later-day Negro Leagues enthusiasts have — with all their perhaps well-meaning efforts — repeatedly clouded the actual (and admittedly substantial) achievements of one of Cuba’s earliest homegrown stars under a haze of Bunyanesque myth and less than substantial epic legend. In the end they seemingly have buried rather than resurrected any true semblance of the doubly if not triply ill-fated Cristóbal Torriente.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted:

Bjarkman, Peter C. A History of Cuban Baseball, 1864-2006 (Jefferson, North Carolina, and London: McFarland & Company Publishers, 2007).

Rucker, Mark, and Peter C. Bjarkman. Smoke: The Romance and Lore of Cuban Baseball (New York: Total Sports Illustrated, 1999).

Online Sources

Martínez de Osaba y Goenaga, Juan A. “Cristóbal Torriente: El Bambino … de Cienfuegos,” online in Cubadebate (March 27, 2014).

Whirty, Ryan. “Who Holds Cristobál’s Fate,” online in: The Negro Leagues Close Up: A Blog About a Century of African American Baseball History (January 27, 2016).

____________. “Torriente: Slavery, Politics, the Sugar Trade and the Search for Answers,” online in: The Negro Leagues Close Up: A Blog about a Century of African American Baseball History (January 21, 2016).

____________. “A Mass Grave for a Baseball Legend?” online in: The Negro Leagues Close Up: A Blog About a Century of African American Baseball History (January 7, 2016).

Notes

1 Jorge S. Figueredo, Who’s Who in Cuban Baseball, 1878-1961 (Jefferson, North Carolina, and London: McFarland & Company Publishers, 2003), and Cuban Baseball: A Statistical History, 1878-1961 (Jefferson, North Carolina, and London: McFarland & Company Publishers, 2003).

2 These are the batting-average numbers provided by James A. Riley (The Biographical Encyclopedia of The Negro Baseball Leagues) for those three seasons. (New York: Carroll & Graf, 1994). But such are the vagaries and inconsistencies of Negro League statistics that these numbers do not at all match those provided by John Holway The Complete Book of Baseball’s Negro Leagues: The Other Half of Baseball History (Fern Park, Florida: Hasting House Publishers, 2001). Riley has Torriente claiming the 1923 Negro National League batting title with a .412 mark, but Holway has him finishing third the same year at .395. Holway’s numbers for Torriente are .361 (1920), .346 (1921), and .393 (1922). No matter which source for Negro League numbers one looks at, it is evident that Torriente was a consistent slugger and posted impressively high numbers. But the lack of any consistent reporting or calculations is enough to cloud any specifics when it comes to measuring the Cuban’s greatness in terms of baseball’s highly cherished yardstick numbers.

3 Riley reports that it was the Cuban’s love of nightlife that caused the American Giants to trade him off to Kansas City before the 1926 Negro National League campaign. Since debauchery rarely affected on-field performance, Torriente stroked the ball at a reported .381 clip and led the new club to a first-half league title. But he then apparently quit the squad in mid-August when the team owner refused to compensate him for a lost or stolen diamond ring. His absence was blamed for a second-half dip in the standings, but after returning, he hit .407 in a losing playoff effort against his former teammates, the Chicago American Giants. At least that is Riley’s version. Again Holway differs (The Complete Book of Baseball’s Negro Leagues), crediting Torriente with only a .371 season’s average (it is not clear if Holway’s numbers reflect only the first half-season or the full year) and a lesser .355 playoff hitting mark.

4 John B. Holway, Blackball Stars (Westport, Connecticut: Meckler Books, 1988), 126.

5 Roberto González Echevarría, The Pride of Havana — A History of Cuban Baseball (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 158-161.

6 One of pre-Castro Cuban baseball’s strongest champions, César Brioso, concedes in the epilogue to his recent celebration of a historic 1947 season (Havana Hardball: Spring Training, Jackie Robinson, and the Cuban League, University Press of Florida, 2015) that “whatever the Cuban League may have lost in autonomy [by merging with Organized Baseball] it more than gained in stability.” Brioso admits that in the first half of the century numerous teams (like Santa Clara, Fé, Matanzas and others) rose to brief prominence only to “fade, withdraw, and disappear forever.”

7 William F. McNeil, Baseball’s Other All-Stars (The Greatest Players From the Negro Leagues, the Japanese Leagues, the Mexican League, and the Pre-1960 Winter Leagues in Cuba, Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic) (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2000).

8 Holway (Blackball Stars) offers an only slightly less meaningful metric when he poses as evidence of Torriente’s slugging skills a table of performance against White big leaguers in 28 barnstorming exhibitions between 1918 and 1919 against White big-league clubs. The reported .311 batting average and three homers in 90 at-bats certainly suggest a skillful batsman. But what more do we make of exhibitions that were a close equivalent to today’s spring-training games. Would any modern-era hitter’s spring-training stats be posited as evidence for stature among the game’s true greats?

9 Again there is a good deal of distortion here in some of the ordained volumes of Blackball history. And there are again all the false assessments of the Cuban winter league of the first half of the century. Donn Rogosin (Invisible Men, 1983; new edition, University of Nebraska Press, 2020) mentions stars like Ruth and Cobb playing in the Cuban circuit, which never happened since their only appearances came in brief preseason exhibition tours. Few White big leaguers of star status played in Cuba. Even in the ’50s the dominating Americans were big-league role players like Spook Jacobs, Rocky Nelson, and Dick Sisler.

10 When it comes to statistics alone, perhaps the biggest downside of the case for Torriente as a Hall of Famer of true Cooperstown stature comes from Holway’s own compilations in the tables found at the end of his own laudatory chapter (Blackball Stars, 133). Compiling known numbers from a two-decade career in North American Negro circuits (excluding all the undocumented barnstorming matches), Holway can report only 57 homers (plus a .338 BA) over 731 documented games and 3,233 plate appearances. Huge parks in Cuba itself explain few long balls on home turf, but the stateside numbers seem less impressive than might be expected. Again the “picture on the cover doesn’t match the one inside.”

11 Whirty writes (in his January 7, 2016, blog entry) that one of his missions is “to direct attention to the possibility that the Cuban Babe Ruth is now the only Hall of Famer buried in an unmarked grave.” The claim itself is not quite correct, of course, because the actual resting place of fellow Cuban Hall of Famer José Méndez is actually also in equal dispute. It is likely that Méndez (or at least the bulk of his bones) rest in a group crypt that houses early-century Cuban ballplayers at the Havana Colon Cemetery. But a marked and undisputed individual gravesite certainly does not exist.

12 A copy was supplied to the author by Ralph Carhart in the fall of 2015, weeks after we had jointly visited the presumed Colon Cemetery resting spot in Havana.

13 The now rather dilapidated ballplayer tombs have been a regular stop of the annual Cubaball tour organized by Canadian SABR member Kit Krieger. Krieger has been personally involved in several efforts to have them restored. It is apparent that some players are interred there but likely in a mass crypt and not individual graves. Méndez and Torriente are two players (along with Antonio García) whose busts appear on one of the tombs. Ralph Carhart (plus this author) revisited this site in 2015 with one of the recent Cubaball tours.

Full Name

Cristóbal Torriente

Born

November 16, 1893 at Cienfuegos, (Cuba)

Died

April 10, 1938 at New York, NY (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.